How to Make your Garden a Haven of Biodiversity

Sustainable Gardening: Strategies for Maintaining a Healthy Garden Ecosystem

Contemplate the generous vegetation in this advanced spring, observe the pollinating insects twirling around the flowers, listen to the songbirds… So many little pleasures when you have a corner of greenery. But not everyone experiences the same vitality and this is very much due to our practices: these are the ones that guarantee the good health of the garden and the ecosystems it contains.

For those who are lucky enough to have a corner of greenery, the period of confinement has offered the opportunity to garden, to indulge in physical exercise or simply – today more than ever – to contemplate. Contemplate the generous vegetation in this advanced spring, its procession of pollinators twirling around the first flowers; contemplate the songbirds giving their voices proudly.

However, not all gardens experience the same vitality. They are first of all a reflection of the surrounding landscapes: a garden bordered by hyper-treated monoculture will shelter biodiversity that is certainly poorer, despite the refuge effect that some species may benefit from.

But the degree of attractiveness depends a lot on our behaviour. It is our practices that guarantee the good health of the garden and the ecosystems it contains.

Our gardens, refuges for people living in the city

Of all the damage we inflict on living things, the disappearance of habitats is surely the most worrying. Every ten years, urban sprawl engulfs an area equivalent to that of a department. The consequences of soil artificialization manifest themselves in several ways: depletion of species diversity and homogenization – the most adaptable thriving at the expense of the most demanding in terms of food and/or habitat.

Faced with these growing pressures, many species find refuge in the least concreted places: urban wastelands, cemeteries, public gardens but also private gardens.

If we take a little height, our backyards, as small as they are, constitute an immense mosaic on the scale of the country. The 17 million French owners of gardens actually collectively manage more than a million hectares. That is an area 4 times larger than that of the Nature Reserves of France.

But it is in the heart of urban areas that our gardens are most useful. Scattered in the middle of concrete areas, they still represent half of urban green spaces in Île-de-France, 36% in Paris and between 24 and 47% in major British cities.

These oases of greenery are capable of offering shelter and cover to multiple species: plants on which insects feed, flowers which attract pollinators, quiet corners for birds, lizards and small mammals.

Better: step by step, the gardens form ecological corridors along which these organisms circulate. According to a recent study, a garden is all the richer in pollinating insects when it is surrounded by other gardens within a perimeter of 50 to 100 meters.

Fewer pesticides, more nectariferous plants

It is still necessary that the said gardens are welcoming. With the desire of city dwellers to reconnect with nature and the awakening of environmental awareness, gardeners are gradually reconnecting with gentle and adapted practices. Ecological criteria are now catching up with aesthetic criteria, underlines a recent survey.

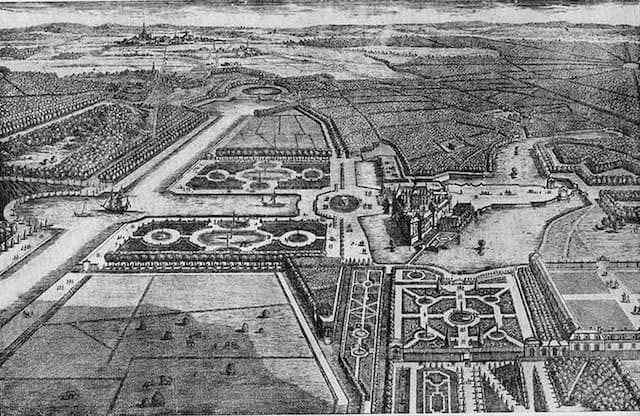

Forty years of zealous use of phytosanitary products have gone by (private gardens represent 9% of French consumption). Our old hexagonal tradition of trimming everything that protrudes, too. What is the “French-style” garden embodied by the magnificent symmetrical works of André Le Nôtre, if not control, work, and ultimately little biodiversity?

The latter, to flourish, requires on the contrary a minimum of management and a maximum of laissez-faire: wild plants, dead wood, bare ground, wasteland… A mosaic of habitats for a multitude of species. In this sense, the traditional English garden, based on the irregularity and diversity of nature, is much more welcoming.

Thanks to biodiversity monitoring carried out every year by tens of thousands of observers participating in the Vigie-Nature citizen science program, we can now quantify these relationships and identify practices that are favourable or not to biodiversity.

We have thus shown that butterfly counters identify on average twice as many species when they do not use pesticides and more individuals.

The explanation? Butterflies, like many flying insects, are very vulnerable to phytosanitary products: directly – through the toxicity of the products – and indirectly, in the case of herbicides which deprive both insects and their larvae of food and refuge.

Among the positive actions: planting plants rich in nectar – brambles, clover, butterfly bushes, cornflowers, lavender, thyme, rosemary, etc.

According to our participatory surveys, the more these nectariferous plants are present in their gardens, the more the observers mention butterflies. However, the fact of reducing pesticides and increasing the diversity of plants in the garden benefits, through a cascading effect, the entire ecosystem. Ecosystem services such as pollination are enhanced. Thus, by extrapolation, if the 17 million gardens activated even these two fundamental levers, the benefits would theoretically be considerable.

Changes through interactions with nature

But how to induce a shift towards virtuous practices on a large scale? To make our gardens true havens of biodiversity, a small cultural revolution must begin.

According to many works in environmental psychology, the mere provision of information is not enough to bring about behavioural changes. “Nature experiences”, in other words, immersion in an ecosystem, attentive observation, and related questions, are a necessary prerequisite for taking action.

How to interpret this evolution? The participants probably established links between the cessation of chemical products, the increase in certain plants and ultimately that of butterflies. Deep nature experiences – here, strong and repeated interactions with butterflies – have come over time to influence behaviours.

Following the Grenelle de l’environnement, the Ecophyto 2008 plan set itself the objective of reducing the use of pesticides by 50% at the national level, within ten years. If the effects of this plan are very disappointing in the agricultural world (the use of phytosanitary products increased by 12% between 2009 and 2016), the sale of these products is now prohibited to individuals.

But there is still a lot to do, individually. These small locally beneficial actions are complementary to environmental policies. Nature protection takes place both in nature reserves and in front of your home. On a large scale, gardens can halt the erosion of biodiversity by restoring connections in urban ecosystems.

The lockdown will have been a good time to make our gardens more welcoming to biodiversity. This also applies to balcony planters, where growing spontaneous plants will be both less expensive and insect-friendly.

Let’s live nature experiences by counting butterflies, bumblebees, and birds thanks to participatory science. Or simply by observing, contemplating what surrounds us, and gardening. Let’s invite biodiversity to settle with us!